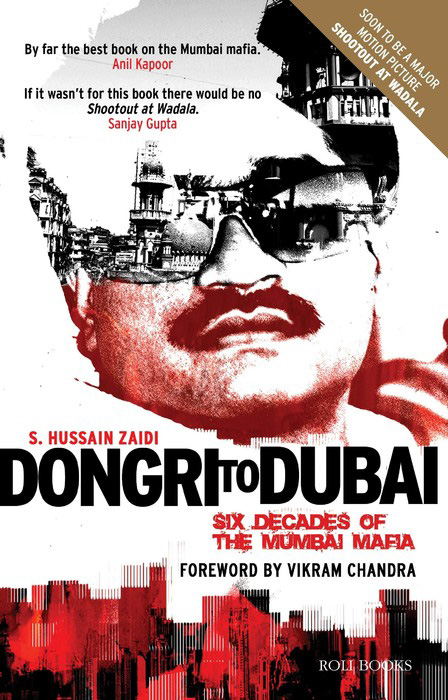

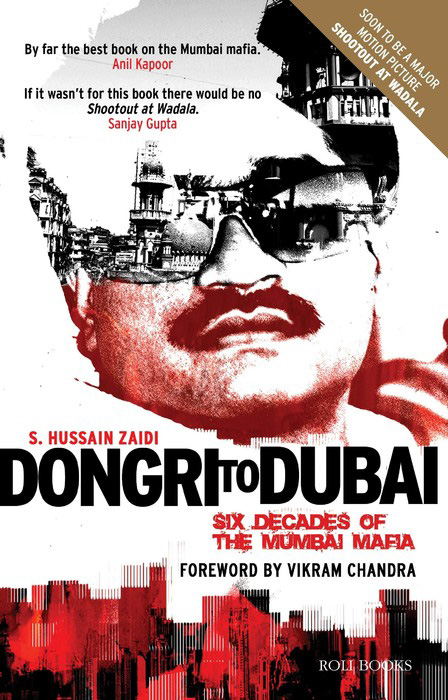

Dongri to Dubai: Six Decades of the Mumbai Mafia is Indian journalist S. Hussain Zaidi’s attempt at chronicling the evolution of India’s underworld. His main focus is the rise of India’s most-wanted fugitive, Dawood Ibrahim, who Zaidi matter-of-factly states is “now living in hiding somewhere in Pakistan.” Zaidi has covered the Mumbai crime scene for nearly two decades while working for The Asian Age, The Indian Express and Mumbai Mirror. He has also written Black Friday and Mafia Queens of Mumbai, books on the 1993 bombings in Mumbai (later turned into a Bollywood movie with the same title) and on women who are part of crime organisations, respectively.

Branded a “global terrorist by US Treasury Department,” Ibrahim was once one of Mumbai’s many mobsters. Although he managed to surpass most of his predecessors while still in his 20s, it was the 1993 blasts which morphed him into an enigma that the Indian state has been unable to solve — perhaps not so much by his design as thanks to the cluelessness of authorities. As is common with major acts of terror anywhere, blame has to be pinned quickly, often turning suspects into one-dimensional outlaws. Ibrahim has, however, has always denied involvement in the blasts.

Beginning the story of Mumbai’s crime world, Zaidi aptly opts for a wide-angle lens. Sketching the slums in post-independence Bombay (as it was then called) of the 1950s, he describes an era sans firearms, when wielding a mere knife yielded enough fear. He profiles colourful personalities who ruled the underworld and its many factions — inspiring the best of celluloid ‘Gabbars’ and ‘Mogambos,’ — way before Dawood Ibrahim Kaskar, son of police constable Ibrahim Kaskar, arrived on the scene. (The fact that Ibrahim is the son of a Bombay cop is itself as cinematic as it gets.)

Stories of the larger than life Haji Mastan who had a knack for striking alliances, sniffing out profitable ventures and brokering rewarding deals offer insight into the workings of shrewd mafia minds. A few examples are the “seven feet tall” Karim Lala who hailed from Peshawar and Madrasi Varda Bhai with an exceptional gift of the gab and the maxim of keeping peoples’ “bellies full and balls empty”.

Constable Kaskar is introduced as a righteous cop who made an honest living and dwelled in a 10 by 10 house with his wife and 12 children in Dongri, south Bombay. Yet there is some contradiction about Kaskar’s persona, who, according to Zaidi, also worked for gangsters, enjoying a certain level of trust with them. Anyone inclined to link Ibrahim’s initiation into crime with his father’s connections may arguably conclude so. With poverty and deprivation destined for the household, Zaidi dissects how the enterprising Ibrahim and elder brother Sabir naturally grew streetwise, learning to con their way in life. He relates some amusing incidents such as when, after meticulous planning, the brothers and their small gang successfully snatch Rs. 500,000 being transported by Mastan’s aides, only to discover it was a bank’s cash consignment.

As Ibrahim steps into the smuggling arena his success gives way to jealousy resulting in Sabir’s murder in 1981 at the hands of the rival Pathan Gang members, Amirzada, Alamzeb and their accomplice Manya Surve. According to Zaidi, Sabir’s murder “opened a new chapter of blood and gore; revenge and broad daylight killings … Dawood not only turned vengeful but intensely motivated and driven, propelling him out of the small league in the Bombay pool and pushing him into the big sea of crime.” Zaidi traces details of several killings that followed, including Surve’s ‘police encounter’ and Amirzada’s assassination inside a full courtroom.

Surve’s character has been portrayed by John Abraham in the Bollywood film Shootout at Wadala, based on some chapters of Zaidi’s book. Using rhetoric to demonise Ibrahim and somewhat going overboard with poetic license, the screen writers lionise Surve, himself a ‘most wanted’ mobster.

Beside incidents of bloodshed, sadistic hit-jobs and broad-daylight assassinations described in ghastly details based on police records and eye-witness accounts, Zaidi also dissects mafia linguistics, for instance the origins of words like supari and Rampurichaku. He also follows intricate tales of backstabbing, both metaphoric and actual and shares extensive details on all key players: from Ibrahim’s one-time top aide Chota Rajan to his current ‘CEO’ Chota Shakeel as well as Shakeel’s protégé Abu Salem who went rogue. His escapades in Bollywood implicated Sanjay Dutt and make for a thrilling read.

Zaidi also outlines Ibrahim’s activities in Dubai, where he has been settled since escaping from India in 1986, enjoying connections with heads of state, crime mafias all over the world and allegedly even Al Qaeda. Meanwhile, the wedding of Javed Miandad’s son with Ibrahim’s daughter catalysed Indian paranoia that he is a “state guest in Pakistan”. For the Pakistani reader, an intriguing aspect of Zaidi’s narration is the recurring emphasis on Ibrahim’s links with the ISI, which Pakistani authorities have categorically denied. Zaidi maintains he is guarded by Pakistan Rangers, has Pakistani passports and lives in a palatial home in DHA, Karachi, under ISI protection.

If survival in this line of work requires exceptional wit, grit and survival instinct, Zaidi’s own conclusion reads like a tribute: “To those who know of Dawood’s might, power, and reach, it’s no surprise that he’s […] more cunning and smarter than most heads of state put together and has the business acumen of several Dhirubhai Ambanis […] If you examined even one aspect of his business and survival skills, you would be convinced that he thinks as fast as lightning.”