Footprints: OUT ON A LIMB

I WAS immersed in monitoring developments at the recent Faizabad sit-in when I got a phone call from an unknown number. It was an international number, so ignoring it in favour of calling back was not an attractive option. Annoyed, I took the call.

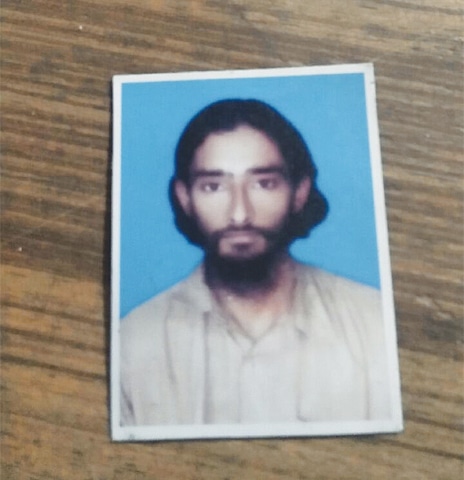

“Hello, I’m Shafaqat Ali, calling from a prison in Malaysia. I have made strenuous efforts to get your number as somebody told me you can really help me,” said the caller.

The sentence, spoken in a deep Punjabi accent, forced me to pay attention.

“Please tell me what I can do for you,” I asked, and he started narrating his story.

Shafaqat went to Malaysia, whose constitution defines Islam as the religion of the federation, in early 2000s from Punjab’s Sheikhupura district. He was working as a caretaker at a palm plantation owned by a Sikh doctor. The latter’s forefathers had migrated from India and then settled here.

According to Shafaqat, on Aug 23, 2011, Shafaqat’s employer Dr Harjit Singh started chatting with him about the raid by the US Navy SEALs in Pakistan’s city of Abbottabad, in which the Al Qaeda leader, Osama bin Laden, was killed. That had occurred just a few months ago that year, in May. According to Shafaqat, during their conversation, Singh commented about Islam in a derogatory way. The discussion heated up.

“I could not tolerate this and killed him,” Shafaqat told me, adding that subsequently he himself called the police after the murder and confessed to his crime.

After his arrest, said Shafaqat, he contacted Pakistan’s embassy in Malaysia for legal assistance; but nobody helped him. He was provided a government lawyer by the High Court in Malaysia’s Penang state. But Shafaqat said that the appointed lawyer did not defend him properly — he had no sympathy for his client. Shafaqat was awarded the death sentence by the high court, which was maintained by a higher appellate court and eventually by the federal court.

Having exhausted all the legal forums available to him, without the benefit of satisfactory legal support or any official assistance by the government of Pakistan, he is now on death row in the Seberang Perai Prison of Penang.

Having heard this story, I contacted Pakistan’s foreign ministry. Dr Mohammad Faisal, the spokesperson, immediately took up the matter with the Pakistan embassy in Malaysia. After checking with the officials there, he stated that the mission had given consular access to Shafaqat. “He was advised to apply for royal clemency for converting his sentence from the death penalty to life imprisonment,” he said. “However, Mr Shafaqat declined the advice and has not applied for royal clemency to date.”

But Shafaqat said that he is still waiting desperately for support so that he can access this last chance of royal clemency. However, nobody has reached out to him yet. “I don’t know whether the Pakistan government is unable to help me or doesn’t want to rescue me,” he said.

According to some recent reports, around 9,000 Pakistanis are languishing in foreign jails. Most of them have been detained for illegal migration and petty crimes, though some are also facing charges of murder and attempted murder. But the murder committed by Shafaqat is unusual.

“Islamic as well as Pakistani laws are clear that nobody can take the law into his own hands. You can’t react to a provocation, even in the realm of religious sentiment, even living abroad, because you have to respect the law of that land,” commented Khurshid Ahmad Nadeem, a socio-religious analyst. He added that all schools of thought in Islam agree that nobody can execute any other person for any crime; it is the jurisdiction of a court of law alone.

“We should teach this to our people, especially those who are going abroad and living in non-Muslim societies, because we can’t afford to have our people getting involved in the religious sentiment dispute in foreign lands either. Those that are in charge of our seminaries and mosques should teach people that they should respect the law. Our schools should teach students that they have no right to act as judges, no matter whether somebody has committed murder in front of them.” Barrister Sarah Belal of the Justice Project Pakistan, a group that provides legal assistance to needy prisoners, says that foreign nationals in any country’s criminal justice system are at a particular disadvantage. “He is a Pakistani facing execution. The government of Pakistan has a constitutional duty to protect the lives of its citizens and to ensure that he is dealt with in accordance with the law at home and abroad, no matter what the alleged crime,” she said.

Published in Dawn, December 17th, 2017