IN the 1970s, a young graduate from Lahore’s University of Engineering Technology was on the lookout for a job. One of his first applications was to the publicly run Pakistan Telephone Company, whose monopoly made owning a telephone in the country a luxury for decades. He recalls that there were several hundred candidates who applied for the same post — a situation that has worsened over time. He found it to be a waste of time and talent.

Later, he got a job as a lecturer at Punjab University. After the imposition of martial law in 1977, the intellectual environment in universities began to deteriorate, reaching the point where one day, his wife (also a lecturer) was dragged out of her class by students aligned with a religio-political party that has terrorised Punjab University since Zia’s days. Persistent threats of death and injury led to the family’s flight from Pakistan. They left with their meagre belongings to embark on an unknown path.

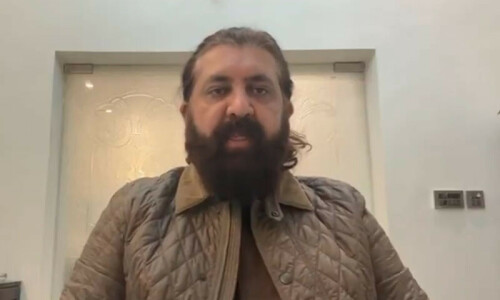

Today, four decades later, the person is recognised as a pioneer in IT. He is a true reflection of a ‘visionary’. One of his early works related to a product design at a company called Trilogy, whose products are a precursor to important software like Nvidia and gaming software and graphics. To demonstrate the extent of his influence, his company NextGen was the first one to truly challenge the monopoly of Intel, a microchip giant. It has the distinction of being the first of only 17 companies to be awarded the title of ‘Cyber Catalyst’. Even Bill Gates and Vinod Khosla found it worthwhile to meet him and acknowledge his stellar contribution. The icing on the cake was that his name was mentioned in the History of Computing compiled by a leading university.

The person’s name is Syed Atiq Raza. But how many in Pakistan have ever heard of him or his achievements? It was only after his appearance at the PIDE PSDE conference at Peshawar that I, and many others, came across his remarkable story. To add, a whole industry grew out of one innovation (micro-processors), leading to newer innovations later. It was Apple that invented PCs, which led to the upending of existing technologies of the time. Micro-processors came to be replaced by software that have now become the dominant mode of work, reflected initially in browsers like NetScape, which led to Microsoft’s Explorer and Google’s Chrome. All these innovative products used research and technological breakthroughs of which Atiq, amongst others, was a part.

There is the vexing question of why the state has never felt the need to retain and nurture its quality human capital.

Barring any error in the explanation of technical aspects, this was a brief introduction to just one person who has left a substantial imprint on technologies that are now a necessary part of our livelihoods, and those which will be an integral part of our economic future.

For a moment, think of what could have been if Atiq had spent all these years in Pakistan and made the same effort here? Just to give you an idea, the semiconductor chip market was valued at $580 billion in 2022, projected to reach $1.1 trillion in 2032 (CMI). Pakistan does not figure anywhere in this huge market — our total trade, imports plus exports, does not even amount to $100bn.

The story narrated above is in the context of why Pakistan has been consigned to the status of an economic laggard who finds it difficult to escape the perennial nazuk mor. Moreover, there is this vexing puzzle of why the Pakistani state has never felt the need to retain and nurture its quality human capital. There is no concise answer, but a few probable explainers do a decent job in unlocking this puzzle. Since the country’s creation, our decision-makers have always been on the lookout for an external cushion, a kind of life insurance that could mitigate the aggregate (as well as personal) risks.

By luck — or bad luck, depending upon one’s perspective — circumstances such as the Korean War, Seato/ Cento, Afghan-Soviet war, 9/11, and recently, China’s Belt and Road Initiative, helped scuttle any push for much-needed economic reforms as the fiscal and external financing squeeze was temporarily alleviated. Along the way, rude shocks like the Pressler Amendment failed to push the system towards transformation.

Why? Because this historical trajectory complemented the colonial economic management well. Two basic tenets of this model are: to solve an issue, throw more money at the problem; and second, continually build brick and mortar infrastructure, especially the big-ticket, long-gestation items that also bring perks like post-retirement, long-term jobs. The former complements the ‘tax more’ mantra, altogether obviating the need for curtailing the plush Mughal-style expenses. The latter necessitates the search for an external ‘sugar daddy’ who can provide dollars. In between, those who call the shots here can (and have) rack up plentiful wealth under official patronage — subsidised land allotments and tariff-protected industries are two prominent examples.

Both of these, though, are discarded strategies that have been thrown into the waste bin of cast-off ideas long ago. But they continue to hold sway here.

Simply put, this model of economic management does not require brilliant, hardworking, innovative people, transformative ideas, creativity or competition. And neither is there an incentive structure — financial or societal — that rewards such traits. The expectation of some external plus divine force relieving us of our troubles is so ingrained at the decision-making level that there is little or no need to retain the country’s outstanding human capital.

This, to a large extent, explains why Pakistan is an economic laggard. Meanwhile, with a ragtag band of mediaeval vandals again laying siege to the capital of a nuclear nation, another ‘operation’, and with recourse to the 25th IMF programme, Pakistan’s economic goose seems to be well and truly cooked.

The writer is an economist and a Research Fellow at PIDE. The op-ed constitutes his personal opinion.

Published in Dawn, July 29th, 2024

Dear visitor, the comments section is undergoing an overhaul and will return soon.